Folktales that nurture and sustain our collective memory.

The telling of Parramisha – stories by Romani families held the Rom Ratt/blood together either as historical events or as everyday warnings about surviving against Romantic fantasy or negative stereotypes. This tradition of storytelling also has kept the Romanes language alive and from completely dying out, as most stories would have Romani words scattered throughout.

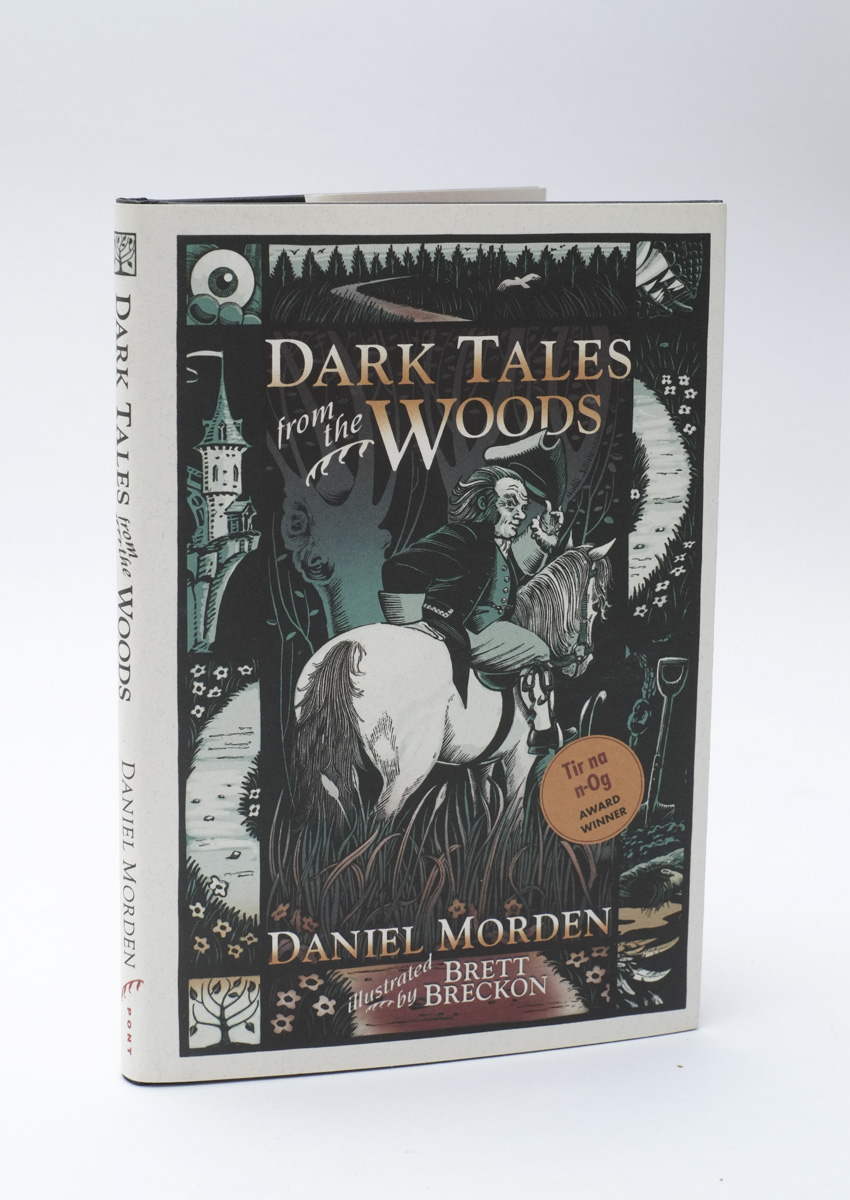

Daniel Morden’s Dark Tales from the Woods carry a foreshadowing of the 1000+ year Diaspora; they are chilling, strange and often uncanny. The Romany/Gypsy stories are Morden’s retelling of seven old folktales, originally attributed to the Welsh Gypsy storyteller Abram Wood. These old folktales were brought to Wales by our Amari puri/ancient ones.

Arriving in Wales in the early 18th Century with Abram Wood, throughout the Diaspora they had carried their world with them and the stories had remained in the oral tradition, never having been written down. The folktales have been handed down the Wood family line for seven generations. Black Ellen Wood, it’s said, knew 400 folktales and could recite all from memory. John Roberts was the first to write the folktales down in Romanes for Francis Hindes Groome, which were published in Groome’s book, In Gipsy Tents. In fairness, it must be said that many other Welsh Romany families valued and engaged in storytelling too.

Most of the stories take place in a forest with the dark woods serving as an undifferentiated ground of being, a place where our psyche has its first life experiences; a place of danger and ordeals, a place of secrets, a place of inversions, or as a sanctuary to hide and find safety within. Perhaps even serving as an atchin tan/stopping place. It’s certainly a place outside of temporal time. An evocation and reminder of where a Romany/Gypsy must learn to navigate a world of inversions that is often hostile to us. These folktales nurture and sustain our collective memory.

The central character of Jack, a rascally chavo/boy and survivor, shows the reader his cunning and good fortune, succeeding in triumphing against powerful adversaries, ending up winning gold and the pretty girl. Morden retells stories where Jack appears in “The Squirrel and the Fox”, “The Fiery Dragon” and “The Green Man.” That traditional rule breaker, the Trickster appears in “The Master Thief.” While women have strong characters, a practicality and wisdom that often saves the day. Mary the maid proves a wily and heroic adversary, spinning riddles and outwitting her handsome deadly suiter. Arwen is guided by her Roma Dya/mother into listening to her dream that becomes a frame story – a story within a story – showing the power of storytelling to transform. An ancient woman guides Jack into his fortunes. The dark feminine is configured as a cruel, murderous and devouring Chavvani/witch. While there are princesses to woo and marry, they are certainly not Disneyfied nor cast as compliant.

There are many episodes in this book that stay with the reader afterwards. In “Mary, Maid of the Mill” a nightmarish story finds young girl under attack from intruders in her own home, betrayed by someone she trusts she rushes in terror into a dark forest. In “The Green Man”, Jack finds that kindness works better than force. In “The Fiery Dragon,” Jack encounters a mighty giant and discovers the danger he’s in. His helper comes from sharing his meal with a lowly dwarf – another inversion. In ‘The Squirrel and the Fox”, Jack and his elder brother Tom part ways, return with very different fortunes. Tom forces Jack to give up his eyeballs along with his gold. An ancient old woman guiding Jack proves she’s anything but divi/mad. A weeping house symbolizes the grieving over a forgotten and lost identity.

The importance of a call to memory cannot be understated. Everyone of Romani/Gypsy descent has been a traveller at some time. The story, Leaves that Hung but Never Grew is about forgetting and remembering who we are as the central theme. It is my favourite storyin Daniel Morden’s book. Remembering who we are is crucial to our heritage and Welsh Romany/Gypsy identity. And specially, imperative in light of subsequent rewriting of history that has judged us invisible

That said, many stories are reminders of Brothers Grimm. Readers will find the usual patterns and echoes of fairytales: The number three is configured into trials, animals talk, maidens shape shift, magical helpers appear, witches are wicked, wise women are wisdom keepers, older brothers compete, disguised heroes appear etc.

The Brothers Grimm re-wrote and tamed old folktales to suit Victorian morality. While Groome and subsequently, Sampson and Yates were willing participants in appropriating and romanticizing the Welsh Gypsies as well as Romanichal stories. Absent from these translations of Matthew Wood’s speaking in Romanes is the vitsa/tribal memory that informs the stories from within.

In contrast, Morden reinvigorates these folktales with intelligence, sensitivity and respect for the inner dynamics of a story; casting remarkable characters and featuring imagery of the Welsh landscape as a context for what is lost and regained. He uses verses and songs, staying true to the Romani way of storytelling around the yog/campfire, which would often have been accompanied by harpists and fiddle players.

Dramatizing the stories are Illustrations in bold black and white line art by Brett Breckon an artist living in West Wales. The clean black and white lines resonate and reiterate the contrasts in the book’s morals, fortunes and goings-on.

Daniel Morden is a Welsh storyteller in the oral tradition. A non-Rom, he respects the power of a great story, stories that have stood the test of time, through the generations. He has avoided the usual cultural tropes and stereotypes giving his readers a healthy, non-ambiguous storytelling set that neither sentimentalizes nor glamorizes.

It’s important to note that these stories were meant to be heard. Morden has performed all over the world, in schools and theatres, at festivals and on the radio. In 2007, Dark Tales from the Woods was awarded the Welsh Books Council’s Tir na n-Og Award. These folktales in spoken word are available on YouTube.

However, Romani story telling isn’t simply intended for entertainment. Our parramisha teaches morals and codes developed over hundreds of years that have helped Romani survive having often been forced from prejudice, as well as extreme hardship to continually keep moving. Romani life in general has survived always on the margins in a necessarily inverted reality. Yes, our tradition of Parramisha – storytelling must never die out. It is us.

Dark Tales from the Woods, Morden Daniel, Pont Books, Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales 2006.

By Frances Roberts Reilly BA (Hons) is a published Romani woman poet, memoirist, playwright and author. She is a direct descendent of Abram Wood.