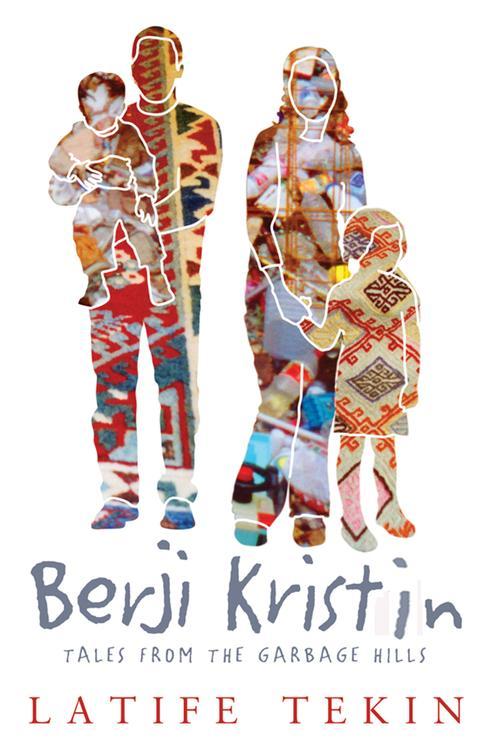

Berji Kristin: Tales from the Garbage Hills

Latife Tekin (trans. Ruth Christie, preface by John Berger, intro. by Saliha Paker)

This novel was originally published in 1984 in Turkish, as Berci Kristin Çöp Masalları, the second in a three–book cycle by the writer Latife Tekin (Dear Shameless Death, and Swords of Icebeing the others, though each is an independent novel in itself). She is one of the most respected authors in the country and cited by modern Turkish prize-winners (such as Elif Shafak and Orhan Pamuk) as a major influence upon their own writing. Often credited with ‘inventing’ Turkish “magical realism” (in comparisons to Gabriel Garcia Marquez), Latife Tekin prefers to see herself as a novelist who represents the unheard, the ‘missing voices’ in Turkish literature, the village people, the rural poor, urban refugees and the Romani people of Turkey (amongst the other minority ethnic and religious communities in the Republic). Her realsim is not so much ‘magical’ as a clear reflection of the world–view adhered to by the people whom she writes about and part of her own life, as she tells us in an introduction by Saliha Paker,

“The school was the men’s living room in our house. I learned to read and write as I played with the jinn under the divans. Jinn and faeries used to live under the divans in Karajefenk [village]… I went to see their homes and their weddings, and learned their language… My mother was a strange woman… was literate… knew Kurdish and Arabic. She used to enquire from the Gypsies that came to our village about places and people unknown to me.”

The ‘Garbage Hills’ in this novel are the location for this community that Latife Tekin knew well, in a place and amongst people “unknown” to her, pushed to the literal edges of a society (Turkey in the 1980’s, during the military coup) and an unnamed city (but understood to be Istanbul), a community that is never identified as a group, but many are clearly Romani (Romanlar in Turkish), Kurds, Arabs, rural migrants, refugees and other ‘outsiders’ struggling to survive and come to terms with their existence, their dreams and their hopes for the future. Characters such as ‘Güllü Baba’ (father from the roses), ‘Kurt Kemal’ (Kemal the Kurd) and Sirma, a mother driven crazy by the loss of her baby in the collapse of a shanty-dwelling, fill these pages, but the central character might be said to be the location itself, as it changes and morphs from the city’s rubbish dump to the urban district of Flower Hill. There are clear signs of the neighbourhood’s origins, even after the change of name – the main route into the mahalle is Rubbish Road; the community mosque has a minaret made of recycled tin cans and ornate doors ‘borrowed’ from some other, older building.

The brutality of the circumstances that the ‘residents’ of the Garbage Hills live in is driven home, with repeated eviction attempts by the local authority, the frequent destruction of the shanty-huts by police, the garbage itself upon which they live, as it poisons them. Snow falls are actually toxic waste from the local factories, which eventually becomes the source of employment for some, though not all of the inhabitants of ‘Flower Hill’, as Rubbish Road and surrounding streets comes to be named in the settlement; one of the inhabitants, Lado the Gambler maintains his independence from waged-labour through a series of escapades. High winds tear off the rooves of the shanty dwellings, taking with them the babies slung in cradles hanging from the temporary rafters, only to be found alive (bar one tiny soul) at the bottom of the hill in the first glimmer of dawn. The novel is an urban fairy–tale; dark, menacing and forbidding (as all good fairy–stories are), yet punctuated by moments of light, humour, laughter and occasional joy, filled with lessons from real life disguised as tales. Sometimes bloody and raw as the wounds from beatings inflicted by the police and baliffs who try to evict the residents of the Garbage Hills, it is a prescient description of the actual, violent evictions in Turkey’s urban regeneration programme that saw hundreds of Romani families pushed further and further from their traditional neighbourhoods and workplaces (Sulukule, Tarlabashı, Küchükbakkalköy, amongst many other places). Portents of the destruction of Dale Farm and other ‘Gypsy’ encampments and stopping places across Europe are very much present in the novel, the confrontation of the state and the undesireable, the urban nomads, the displaced and dispossessed, the shift from urban space to battle–space, as Edward Sa’id called it in his Lothian Lecture series of the early nineties.

In preparation for this novel Latife Tekin interviewed many of the people who had experienced the urban upheaval of the 1960’s in Turkey’s dramatic industrialisation of the period. Her characters are drawn from life experiences and lived expertise, as anthropologists like to categorise such knowledge when they find it in their research, to repackage the wisdom of these struggles that ordinary and frequently desperate people live through, encapsualting the results as ‘resilience’ rather than resistance, and ‘defence’ of cultures and traditional ways of life, rather than seeing the defiancethat the dispossessed and dislocated maintain in the face of discrimination and persecution in Europe. Latife Tekin does not shy away from these harder, harsher realities of resistance and defiance, but this is a social not socialist realism; it is not the preachy intellectual, 1950’s social commentary of the ‘kitchen sink’ dramas, as it retains the fantastical of Ali Baba or Aladdin. The novel is one of hope and aspiration, as well as destruction, as the squatters of the Garbage Hills become the residents of Flower Hill, agents of their own change, on their own terms, and in this mixture of loss and longing with love and life, the novel finds its great power, its substance and strength. Like the dark tales of Abram Woods and other Romani story–tellers of the past, there is less dialogue and more description than might normally be expected in a novel, but that is the point of the tale; it harbours both the spirit of traditional stories and story–telling and the energy, the vitality of the characters that inhabit the narrative, in the realism of the modern novel. As a testament to this vibrancy of the Romani people in Turkey (as across the world) and all those pushed aside by development, regeneration and urban renewal, this is one of the best representations that I know…

By Dr Adrian Marsh, Istanbul